.

The Alliance with Mata'afa in Samoa, 1888-1889

December 6, 2014

In 1888 and 1889, U.S. warships, operating under orders to protect American lives and property, began to conduct active military operations to defend a rebel army in Samoa led by Mata'afa Iosefo. Mata'afa was fighting against the German-backed Tamasese regime.

Tensions in 1888 led the United States to dispatch three ships to Apia in 1889, all three of which were lost or damaged during a hurricane. These losses were startlingly when compared to the U.S. interests in Samoa. One ship, the USS Nipsic, was the first ship in the Navy to have electric lights, which cost $5000 to install. This sum was larger than the biggest commercial complaint against the German-backed government. The machinery on board the USS Vandalia was worth about three times the value of the largest single American investment in Samoa. And, the estimated amount to buy all of Samoa from Germany was about 330,000 pounds, or roundabout 1.7 million dollars, which was about half of the total value lost in that single day for the United States alone. This does not count the three German ships.

I assume the lights on the Nipsic (pictured on the right) were lost.

USS Nipsic

This post briefly explains the origins and nature of informal cooperation between Mata'afa and the U.S. Navy in 1888.

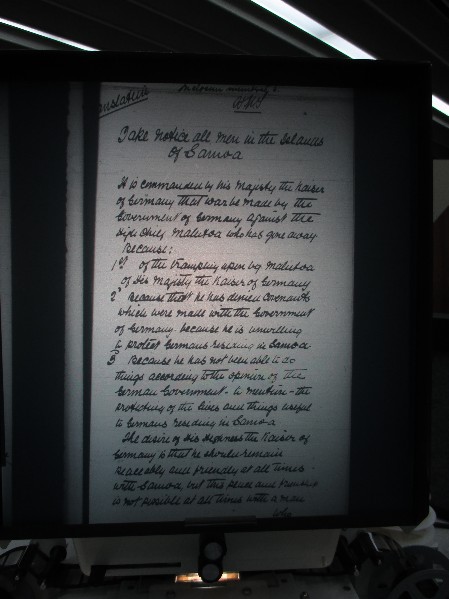

A bit of background is necessary. Beginning in the 1870s, there was a commercial competition between the United States, Germany, and the British in Samoa, centering on the island of Upolu. In 1887, a German firm in Samoa helped a rebellion led by Tamasese to overthrow the Malietoa. During the conflict, Germany "declared war" against the Malietoa, the leader in Samoa, and helped recruit, train, and arm Tamasese's forces (see the "Declaration" on the left). Once Tamasese gained power, he selected Eugene Brandeis, formerly a clerk in the German firm in Samoa, as his Premier. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the former clerk for the German firm favored German commercial interests over American, leading to constant outcries from American merchants.

The standard story of intervention in Samoa, perhaps best described by Paul Kennedy's in his Samoan Tangle, concentrates on great power diplomacy and the international conferences dedicated to Samoa. The action in his story is largely in Berlin and Washington.

The origins of the alliance between the U.S. Navy and Mata'afa were located in Apia and not Washington.

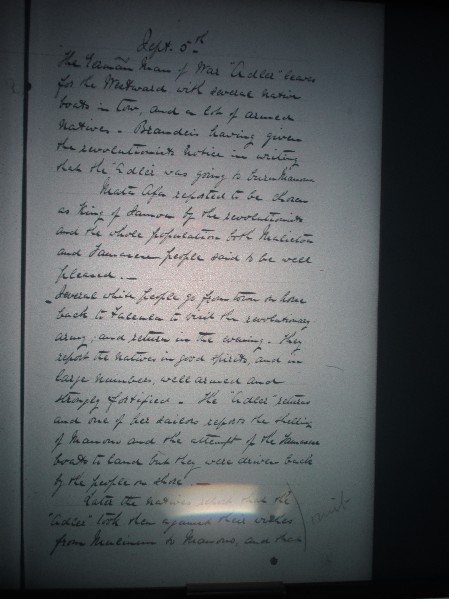

In August and September 1888, many Samoans rebelled against the Tamasese regime, selecting Mata'afa as their leader. The report on the right is the U.S. Vice Consul's dispatch, who describes the fast moving events. As Samoans quickly began to join Mata'afa, the German Navy increasingly intervened to preserve the Tamasese regime's position.

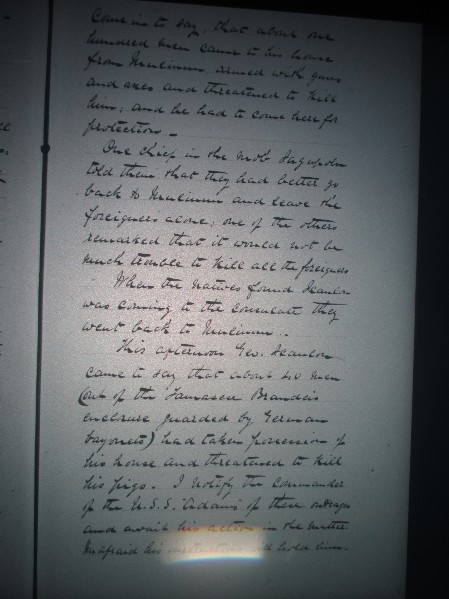

The only U.S. ship in port was the USS Adams, commanded by Richard Leary. Throughout September, the Adams' crew watched as German warships became increasingly active, bombarding Mata'afa's forces, sinking canoes, ferrying troops, and fortifying Tamasese's positions. Leary protested German intervention, although he did nothing tangible. The letter on the left represents one instance of these protests, where he describes the actions of a German ship (the Adler) as violating international law by actively intervening in the islands.

Leary likely wanted to intervene but couldn't. His orders said he could only intervene to protect American lives and property. So long as the Germans did nothing to hurt an American, Leary would have to wait and do nothing.

All of this changed on October 6, when some of Tamasese's warriors went to the home of Charles Scanlon. Scanlon was pro-American, an argument happened, and it got heated. It ended with the warriors holding Scanlon's pigs at gun point. Scanlon ran to the U.S. Vice Consul, demanding protection. Here the story has an interesting legal feature. The State Department and U.S. Consulate had decided against the Scanlon family's citizenship claims years earlier, in part because they could not show naturalization papers, and in part because Charles and his brother had a Samoan mother. Yet, in the crisis that October, Blacklock and Leary were more than willing to use force defend Scanlon.

All of this changed on October 6, when some of Tamasese's warriors went to the home of Charles Scanlon. Scanlon was pro-American, an argument happened, and it got heated. It ended with the warriors holding Scanlon's pigs at gun point. Scanlon ran to the U.S. Vice Consul, demanding protection. Here the story has an interesting legal feature. The State Department and U.S. Consulate had decided against the Scanlon family's citizenship claims years earlier, in part because they could not show naturalization papers, and in part because Charles and his brother had a Samoan mother. Yet, in the crisis that October, Blacklock and Leary were more than willing to use force defend Scanlon.

Robert Louis Stevenson (the author of Treasure Island), who moved to Samoa a few years later and befriended many of the participants, provides a more detailed (and more gripping) account of the pigs. While the work is not entirely accurate, it makes for a wonderful read.