Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs

George Washington University

Department of Political Science

21115 G. St. NW, 440 Monroe Hall

Washington, DC 20052

ericgryn [at] gwu.edu

| Home | CV | Research | Teaching | Non-State Allies |

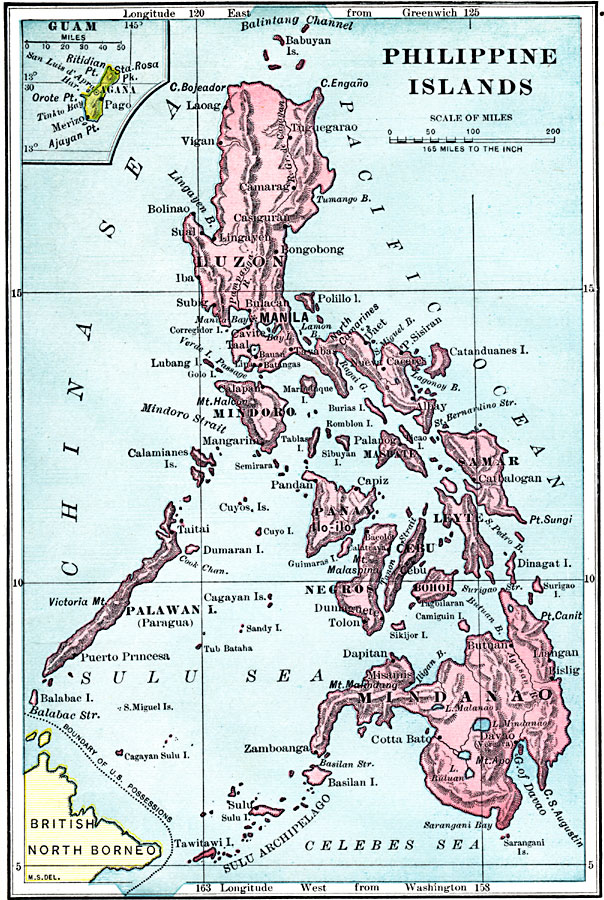

| During the

Philippine-American War, the United States successfully

recruited Philippine units across the islands. The Macabebe were

the most successful. Here I describe Lowe's Scouts, one of the

least successful. Lowe's Scouts was considered an "experiment." They were recruited from Tagalogs, who were of the same language speaking population as the insurgents fighting against the United States. They were from Luzon, the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. On the right is a 1899 map of the Philippines, showing Luzon in the north. |

|

|

The best account of the Lowe's Scouts

service is a book written by Major Edward O'Reilly describing his

service with the Scouts. He called it Roving

and Fighting (1918). He describes the missions of the Lowe's Scouts that he witnessed. The book is written in the style of American military memoirs in the Philippines, filled with useless adventures that are difficult to swallow. But in between daring-do with little purpose, a clear story of the scouts and their history emerges. The first efforts to recruit the scouts were largely a failure. The company was originally composed of forty white soldiers, with only 13 native scouts enlisted. Slowly, more joined and the proportion of white scouts declined sharply. The scouts did what scouts often did. They served as an advanced guard, guides, and did messenger service. They also fought. Sadly, O'Reilly spends more time on funny stories of daily life than chronicling the achievements of the scouts, and when he describes the scouts, he emphasizes the white officers. O'Reilly is pictured on the left. |